Bilge Yabancı on Turkey's civil society under siege

Bilge Yabancı on “Civil Society and Authoritarianism: Co-optation, Repression and Contestation in Turkey” (Edinburgh University Press)

Listen to Turkey Book Talk: Apple Podcasts / Spotify / PodBean / Stitcher / PlayerFM / Listen Notes

What did you set out to achieve with this book?

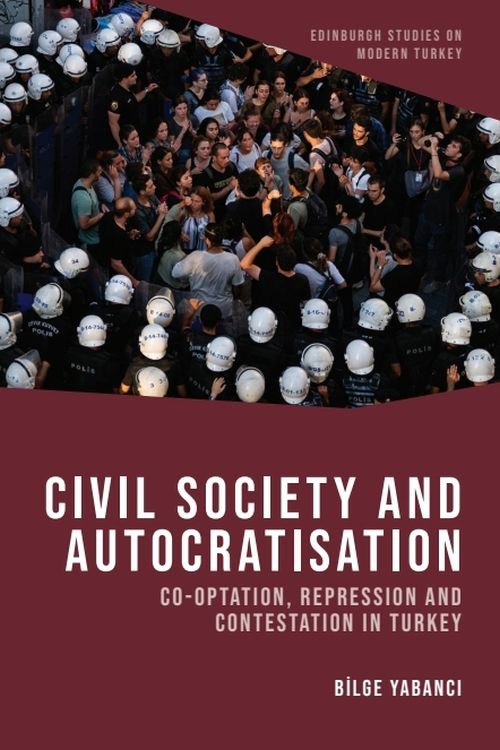

When I started the project, I was already working to a certain extent on what's going on in Turkey as a scholar of political science and political sociology, but also as a citizen. So I think the entire project started as partly my observations of what's going on in reality, and partly my knowledge of what is written in the literature about developments. It was some years after the 2013 Gezi demonstrations, when civil society started to face an increasing crackdown. In the Gezi protests, the government realised the power of independent mobilisation and independent civil society as a venue that can breed dissent and civic opposition from the grassroots. But also it was one year after the failed coup attempt. This was another major turning point for civil society in Turkey. The government started cracking down not only on the perpetrators of the coup attempt, but also several dimensions of civil society. Protests were banned partially or totally in many cities. There was a state of emergency. For me, this was an important moment to start understanding the transformation of civil society.

I had a discomfort about the way autocratisation in Turkey – as well as beyond Turkey actually - is discussed. We explicitly talk about elections, parties and the judiciary, but civil society is usually only briefly mentioned in the autocratisation literature. It is usually mentioned as just a victim of crackdowns, as only a target of the autocratising government's anger. But if you look at the reality, there is actually a puzzling development: There has been an expansion of civil society. I'm not only talking about the number of associations, where we can see there has been an increase in the number of registered civil society organisations in Turkey during AKP rule, but also there has been an expansion of civil society as a space. The number of issues being discussed during AKP rule, including the Armenian genocide, Kurdish rights, LGBT rights, women's rights, environmental issues and labour rights. There have been a number of issues that are more intensively discussed within civil society. So on the one hand, we see an increasing crackdown on civil society, but also an expansion in terms of the number of organisations and the issue areas.

Another issue that motivated me to delve into this project, to look into civil society and autocratisation, is the discrepancy between the classical literature on civil society and the reality. In the classical civil society literature, civil society is defined as an independent field that brings together like-minded and democratic actors, progressive forces flocking to put up a defence against malign autocrats or corrupt governments. This widespread belief in mainstream civil society scholarship, which was dominated by the liberal wave after the Cold War, that sits a bit oddly when you look at civil society in many countries, including Turkey.

What extra challenges did conducting the research after 2016 coup attempt pose?

There was a state of emergency and it was late 2017 when I first started the field work. I first did the desk research, identifying several organisations that I could try to speak with. This included activist groups that were under a crackdown, mostly those working on human rights, Kurdish rights, women's issues, LGBT issues, and the environment. But on the other hand there is an entire set of organisations that work on several other issues and do not deny their close ideological, political ties to the government. I wanted to speak with both types of organisations.

I must say that I found it much more difficult to make contacts with organisations that are close to the government. I didn't expect that, to be honest. Because I tried to contact them through the normal fieldwork protocol we do in research, which means sending an official request, explaining the research project, explaining the ethical background checks, and then asking for an official interview. Since they are not subject to any crackdown, they have nothing to hide from the government or from scholars, so I thought they would be open to speaking to me. If you look at their web pages and the way they appear in the media, they seem like very professional, open, transparent organisations. So I didn't expect it to be as difficult as it was. Maybe it was more difficult because I was affiliated with a foreign university, or maybe because they never received such requests. Back then there were not many people interested in interviewing them. So it was rather difficult to make the first entry point with them. Therefore I changed some strategies and started contacting first the female members, asking them to introduce me to their colleagues. I also started turning up to their public events, trying to make contact. So I overcame this part.

In contrast, there was no avoidance among the organisations that work on rights and other issues that the government may not be willing to hear criticism on. On the contrary, they were very willing to talk to me, despite all the ongoing crackdowns. They know how researchers approach the topic and they know that we guarantee full anonymity. So there was no issue in reaching out to them. They were willing to speak with me, whether it be women's organisations or those working on environmental issues or other issues. Although there were clear cases of a crackdown, they wanted to make their voices heard, to be analysed, to be out there. So they were more willing to speak.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Turkey Book Talk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.